William Morris "Billy" Hughes, 1862 – 1952.

William Morris "Billy" Hughes, 1862 – 1952.

"Goodbye Democracy"

William Morris Hughes (1862-1952) was born in London the only child of William Hughes and Jane Morris. Hughes would later migrate to Australia after his upbringing in Great Britain and 1901 he would be elected to the first federal Parliament of 1901 as member of West Sydney and was an early advocate of compulsory universal training in Australia.[i] In Parliament he proved to be a captivating orator and astute politician and was unanimously awarded the position of Prime Minister in October 1915 after Andrew Fisher resigned due to failing health.

As Prime Minister Hughes was energetic in attempting to boost enlistment in Australia and promoted greater co-operation with the other dominions of the British Empire in order to put greater economic pressure on Germany. Upon his return to Australia after a tour of Great Britain and the front in Europe Hughes reached the conclusion that the introduction of compulsory military service would be the surest method of increasing Australia’s dwindling reinforcement numbers. It became unthinkable to Hughes that Australians could let the men on the front down and was thus positive of support amongst the national electorate.[ii] However support within the Labor Party was not a definite assurance. A bill to introduce conscription would, it was believed be passed through the Lower House of Parliament with the majority of support coming from the opposition party, but would not be successful in the Senate due to Labor defectors. As such it was deemed possible that given the political format of the federal Parliament in 1916 the proposition to introduce conscription could not be enacted upon. It would mean that the Defence Act of 1911 which allowed for compulsory military training for all men of military age but forbade compulsory service overseas. Hughes opened a campaign to introduce conscription through a referendum on 18 September 1916 with voting to be held on 28 October. If successful the referendum would give Hughes a legitimate mandate to override any opposition to conscription from the Senate.

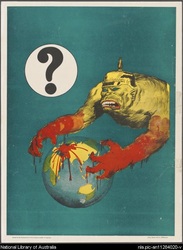

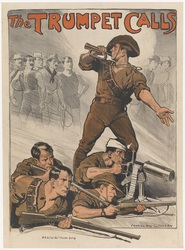

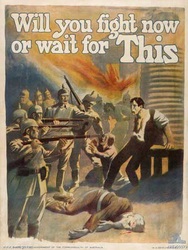

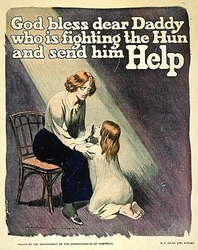

Hughes campaigned nationwide in an attempt to promote the conscriptionist cause, arguing that that Australia needed to supply 5,500 men a month in order to maintain Australia’s divisions in France and the Middle East at near full strength.[iii] This campaign was emotive and Hughes was enthusiastically backed by conservative political parties, a fact which would alienate him from his own party and would lead to his eventual expulsion. Advertising campaigns were effective, especially those produced by Norman Lindsay Hughes campaign in Queensland was largely unsuccessful due to the States political stand against conscription and the makeup of its electorates. The Referendum asked the public:

“Are you in favour of the Government having, in this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in regard to requiring their military service, for the terms of this War, outside the Commonwealth, as it now has in regard to military service within Australia?”

This referendum was defeated however by a slight majority of 1,160,033 against and 1,087,557 in favour. Hughes was, for his activism of conscription ousted from the Australian Labor Party. However the issue of conscription was not wholly resolved and the Australian people went again to the ballot on 20 December 1917. This campaign was characterized by a degree of ferocity and loathing previously unheard of in Australian politics. This was demonstrated when Hughes was struck by egg at a rally at the Warwick train station in Queensland.[iv] The second plebiscite was defeated by a greater majority of 1,181,747 against conscription and 1,015,159 in favour. The referenda were politically divisive across the nation and in Queensland specifically and the final plebiscite closed the issue of conscription permanently.

[i] Fitzhardinge, L. F., William Morris Hughes : a political biography. I, That fiery particle, 1862-1914. (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1964). 202.

[ii] Fitzhardinge, L. F,. The Little Digger: A Political Biography of William Morris Hughes (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1979). 173.

[iii] Jauncy, L., The Story of Conscription in Australia. (Melbourne: Macmillian, 1968). 191.

[iv] Murphy, D. J. Thirteen minutes of national glory - the Warwick Egg Incident, 1917. Queensland Heritage, 3 3 (1975): 15-18.

William Morris Hughes (1862-1952) was born in London the only child of William Hughes and Jane Morris. Hughes would later migrate to Australia after his upbringing in Great Britain and 1901 he would be elected to the first federal Parliament of 1901 as member of West Sydney and was an early advocate of compulsory universal training in Australia.[i] In Parliament he proved to be a captivating orator and astute politician and was unanimously awarded the position of Prime Minister in October 1915 after Andrew Fisher resigned due to failing health.

As Prime Minister Hughes was energetic in attempting to boost enlistment in Australia and promoted greater co-operation with the other dominions of the British Empire in order to put greater economic pressure on Germany. Upon his return to Australia after a tour of Great Britain and the front in Europe Hughes reached the conclusion that the introduction of compulsory military service would be the surest method of increasing Australia’s dwindling reinforcement numbers. It became unthinkable to Hughes that Australians could let the men on the front down and was thus positive of support amongst the national electorate.[ii] However support within the Labor Party was not a definite assurance. A bill to introduce conscription would, it was believed be passed through the Lower House of Parliament with the majority of support coming from the opposition party, but would not be successful in the Senate due to Labor defectors. As such it was deemed possible that given the political format of the federal Parliament in 1916 the proposition to introduce conscription could not be enacted upon. It would mean that the Defence Act of 1911 which allowed for compulsory military training for all men of military age but forbade compulsory service overseas. Hughes opened a campaign to introduce conscription through a referendum on 18 September 1916 with voting to be held on 28 October. If successful the referendum would give Hughes a legitimate mandate to override any opposition to conscription from the Senate.

Hughes campaigned nationwide in an attempt to promote the conscriptionist cause, arguing that that Australia needed to supply 5,500 men a month in order to maintain Australia’s divisions in France and the Middle East at near full strength.[iii] This campaign was emotive and Hughes was enthusiastically backed by conservative political parties, a fact which would alienate him from his own party and would lead to his eventual expulsion. Advertising campaigns were effective, especially those produced by Norman Lindsay Hughes campaign in Queensland was largely unsuccessful due to the States political stand against conscription and the makeup of its electorates. The Referendum asked the public:

“Are you in favour of the Government having, in this grave emergency, the same compulsory powers over citizens in regard to requiring their military service, for the terms of this War, outside the Commonwealth, as it now has in regard to military service within Australia?”

This referendum was defeated however by a slight majority of 1,160,033 against and 1,087,557 in favour. Hughes was, for his activism of conscription ousted from the Australian Labor Party. However the issue of conscription was not wholly resolved and the Australian people went again to the ballot on 20 December 1917. This campaign was characterized by a degree of ferocity and loathing previously unheard of in Australian politics. This was demonstrated when Hughes was struck by egg at a rally at the Warwick train station in Queensland.[iv] The second plebiscite was defeated by a greater majority of 1,181,747 against conscription and 1,015,159 in favour. The referenda were politically divisive across the nation and in Queensland specifically and the final plebiscite closed the issue of conscription permanently.

[i] Fitzhardinge, L. F., William Morris Hughes : a political biography. I, That fiery particle, 1862-1914. (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1964). 202.

[ii] Fitzhardinge, L. F,. The Little Digger: A Political Biography of William Morris Hughes (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1979). 173.

[iii] Jauncy, L., The Story of Conscription in Australia. (Melbourne: Macmillian, 1968). 191.

[iv] Murphy, D. J. Thirteen minutes of national glory - the Warwick Egg Incident, 1917. Queensland Heritage, 3 3 (1975): 15-18.

Thomas Joseph Ryan, 1876-1921.

Thomas Joseph Ryan, 1876-1921.

"You Labor Rat"

Thomas Joseph Ryan (1876-1921), served as the Premier of Queensland during the First World War. Original from Victoria he was born in 1876 at Boothapool, near Port Fairy. His father, Timothy Joseph Ryan was an illiterate Irish immigrant who fostered a strong awareness of politics amongst his six children.[i] Thomas Ryan would study at St Francis Xavier College, and later the University of Melbourne where he would graduate with an arts degree in 1897. Later Ryan would return to the University of Melbourne where he completed a law degree in 1899. Ryan's legal practice advocated workers compensation where he would reputation amongst various trade unions and awakened him politically. He would join the Labor Party, gaining the leadership in opposition in 1912 and winning the Queensland election in 1915.

The First World War brought on a crisis in supplying and sustaining Australia’s war effort. Ryan's Queensland government immediately overcame this issue and was unabashedly pro-war and active in recruitment campaigns. From the moment Ryan was elected Premier enthusiastically threw Queensland’s industries into the war effort to defeat Germany. He was able to mobilize Queensland’s manpower and economy through the voluntary recruitment campaigns which spanned the state and in the guaranteed supply of meat to Britain.[ii] In 1916 he like Hughes also visited Australian servicemen on the Western Front and took part in numerous public debates where he began to develop a political opinion contrary to that of Hughes who believed compulsory enlistment would benefit the war effort. Ryan spoke remorsefully of Britain’s adoption of conscription stating that it was a “temporary arrangement to win the win … rather than as a principle of social reform.”[iii] In 1916, after the announcement of the first conscription referendum labour supporters in Queensland decisively opposed the issue of conscription and Billy Hughes stance. Ryan however maintained silent until Hughes Manifesto of 18 September confirmed that there would be no conscription of wealth in the government’s proposal.[iv] This would confirm that the majority of conscripts would be of working class backgrounds with no provisions of a higher tax rate for the wealthy in order to shoulder the burden. Ryan like many anti-conscriptionists supported the campaign for additional recruits but only on a voluntary basis and that all Australians, regardless of class or economic standing should accept the tax in order to sustain the war effort.

As the only Labor premier in Australia at the time, Ryan was likewise the only Premier to oppose conscription and thus attracted considerable opprobrium from conservative commentators in Queensland.[v] Elsewhere in the country the Labor Party suffered a sizable split over conscription, including in Hughes federal Australian Labor Party. Contrary to this Ryan was able to establish an almost unified party throughout the course of the conscription debates despite numerous accusations of treachery and allying with the German’s. Only two cabinet ministers and five other caucus members openly favoured conscription out of the entire Queensland labour movement.[vi] The State Government in Queensland lent significant support to the labour press which was able to reduce the propaganda of conscriptionists and conservative supporters.[vii] Queensland was labelled as the most ‘Catholic State’ in the Commonwealth, due to the overwhelming support given to Ryan’s anti-conscription campaign from Catholic workers, the Roman Catholic Church and Irish communities.[viii] Queensland recorded the third largest ‘No’ majority in Australia totaling 158,051 against defeating a ‘Yes’ minority of 144,200.[ix]

The conscription referendum of 1917 intensified the debates between Ryan and his anti-conscriptionist cohorts including Archbishop Dr Daniel Mannix, and Archbishop James Duhig. On conscription Ryan spoke widely and energetically which would spill over into the relations between Queensland and Hughes Federal Government affecting the policies of stabilizing the sugar industry and fixing a fair price for sugar growers.[x] Hughes would attempt to charge Ryan with conspiracy over the Hansard incident where Ryan attempted to dodge the censorship laws imposed by the Federal Government. The second referendum was in December 1917 defeated again, this time by a larger ‘No’ majority with 168,875 Queenslanders voting against conscription and only 132,771 supporting the proposal.[xi] The ‘No’ majority gained further support from the sugar industry, small farmers and the fact that twenty-five percent of Queensland’s rural population consisted were Roman Catholic or of Irish descent and a significant proportion of Queensland’s population being of German ancestry.[xii] As a result of these two conscription plebiscites Ryan emerged as major political figure in the nation.

[i] Murphy, D, J., T J Ryan: A Political Biobraphy, (St Lucia; University of Queensland Press, 1975). 11.

[ii] Robinsn to Denham, 6 August 1914, item 16/12804, PRE/61, QSA; Murphy, T J Ryan, 95.

[iii] Raymond Evans, Loyalty and Disloyalty: Social and Ideological Conflict in Queensland During the Great War, (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1981), 235.

[iv] Evans, Loyalty and Disloyalty, 247.

[v] Jauncey, L. C., The Story of Conscription in Australia. (South Melbourne; Macmillian of Australia, 1968).

195.

[vi] Murphy, T J Ryan, 189-191.

[vii] Evans, Loyalty and Disloyalty, 271.

[viii] Evans, Loyalty and Disloyalty, 235.

[ix] Parliamentary Library (2011) Parliamentary Handbook of Commonwealth of Australia: 43rd Parliament. Government Printing Office.

[x] Fitzgerald, R., From 1915 to the early 1980’s: A History of Queensland, (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1984). 6.

[xi] Parliamentary Library (2011) Parliamentary Handbook of Commonwealth of Australia: 43rd Parliament. Government Printing Office.

[xii] Fitzgerald, From 1915 to the early 1980’s, 8.

Thomas Joseph Ryan (1876-1921), served as the Premier of Queensland during the First World War. Original from Victoria he was born in 1876 at Boothapool, near Port Fairy. His father, Timothy Joseph Ryan was an illiterate Irish immigrant who fostered a strong awareness of politics amongst his six children.[i] Thomas Ryan would study at St Francis Xavier College, and later the University of Melbourne where he would graduate with an arts degree in 1897. Later Ryan would return to the University of Melbourne where he completed a law degree in 1899. Ryan's legal practice advocated workers compensation where he would reputation amongst various trade unions and awakened him politically. He would join the Labor Party, gaining the leadership in opposition in 1912 and winning the Queensland election in 1915.

The First World War brought on a crisis in supplying and sustaining Australia’s war effort. Ryan's Queensland government immediately overcame this issue and was unabashedly pro-war and active in recruitment campaigns. From the moment Ryan was elected Premier enthusiastically threw Queensland’s industries into the war effort to defeat Germany. He was able to mobilize Queensland’s manpower and economy through the voluntary recruitment campaigns which spanned the state and in the guaranteed supply of meat to Britain.[ii] In 1916 he like Hughes also visited Australian servicemen on the Western Front and took part in numerous public debates where he began to develop a political opinion contrary to that of Hughes who believed compulsory enlistment would benefit the war effort. Ryan spoke remorsefully of Britain’s adoption of conscription stating that it was a “temporary arrangement to win the win … rather than as a principle of social reform.”[iii] In 1916, after the announcement of the first conscription referendum labour supporters in Queensland decisively opposed the issue of conscription and Billy Hughes stance. Ryan however maintained silent until Hughes Manifesto of 18 September confirmed that there would be no conscription of wealth in the government’s proposal.[iv] This would confirm that the majority of conscripts would be of working class backgrounds with no provisions of a higher tax rate for the wealthy in order to shoulder the burden. Ryan like many anti-conscriptionists supported the campaign for additional recruits but only on a voluntary basis and that all Australians, regardless of class or economic standing should accept the tax in order to sustain the war effort.

As the only Labor premier in Australia at the time, Ryan was likewise the only Premier to oppose conscription and thus attracted considerable opprobrium from conservative commentators in Queensland.[v] Elsewhere in the country the Labor Party suffered a sizable split over conscription, including in Hughes federal Australian Labor Party. Contrary to this Ryan was able to establish an almost unified party throughout the course of the conscription debates despite numerous accusations of treachery and allying with the German’s. Only two cabinet ministers and five other caucus members openly favoured conscription out of the entire Queensland labour movement.[vi] The State Government in Queensland lent significant support to the labour press which was able to reduce the propaganda of conscriptionists and conservative supporters.[vii] Queensland was labelled as the most ‘Catholic State’ in the Commonwealth, due to the overwhelming support given to Ryan’s anti-conscription campaign from Catholic workers, the Roman Catholic Church and Irish communities.[viii] Queensland recorded the third largest ‘No’ majority in Australia totaling 158,051 against defeating a ‘Yes’ minority of 144,200.[ix]

The conscription referendum of 1917 intensified the debates between Ryan and his anti-conscriptionist cohorts including Archbishop Dr Daniel Mannix, and Archbishop James Duhig. On conscription Ryan spoke widely and energetically which would spill over into the relations between Queensland and Hughes Federal Government affecting the policies of stabilizing the sugar industry and fixing a fair price for sugar growers.[x] Hughes would attempt to charge Ryan with conspiracy over the Hansard incident where Ryan attempted to dodge the censorship laws imposed by the Federal Government. The second referendum was in December 1917 defeated again, this time by a larger ‘No’ majority with 168,875 Queenslanders voting against conscription and only 132,771 supporting the proposal.[xi] The ‘No’ majority gained further support from the sugar industry, small farmers and the fact that twenty-five percent of Queensland’s rural population consisted were Roman Catholic or of Irish descent and a significant proportion of Queensland’s population being of German ancestry.[xii] As a result of these two conscription plebiscites Ryan emerged as major political figure in the nation.

[i] Murphy, D, J., T J Ryan: A Political Biobraphy, (St Lucia; University of Queensland Press, 1975). 11.

[ii] Robinsn to Denham, 6 August 1914, item 16/12804, PRE/61, QSA; Murphy, T J Ryan, 95.

[iii] Raymond Evans, Loyalty and Disloyalty: Social and Ideological Conflict in Queensland During the Great War, (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1981), 235.

[iv] Evans, Loyalty and Disloyalty, 247.

[v] Jauncey, L. C., The Story of Conscription in Australia. (South Melbourne; Macmillian of Australia, 1968).

195.

[vi] Murphy, T J Ryan, 189-191.

[vii] Evans, Loyalty and Disloyalty, 271.

[viii] Evans, Loyalty and Disloyalty, 235.

[ix] Parliamentary Library (2011) Parliamentary Handbook of Commonwealth of Australia: 43rd Parliament. Government Printing Office.

[x] Fitzgerald, R., From 1915 to the early 1980’s: A History of Queensland, (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1984). 6.

[xi] Parliamentary Library (2011) Parliamentary Handbook of Commonwealth of Australia: 43rd Parliament. Government Printing Office.

[xii] Fitzgerald, From 1915 to the early 1980’s, 8.